Cleveland Clinic researchers discover a new way to restore movement sensation in patients with upper limb amputations

April 2018.- A team of researchers led by Cleveland Clinic has published the first findings of its kind in Science Translational Medicine on a new method to restore the sensation of natural movement in patients with prosthetic arms.

Directed by Paul Marasco, Ph.D., the research team has successfully designed a feeling of complex hand movement in patients with upper limb amputations. This progress can improve the ability to control your prostheses, independently manage the activities of daily living, and improve the quality of life.

“By restoring the intuitive sensation of limb movement, the sensation of opening and closing the hand, we can blur the lines between what the brains of patients perceive as ‘I’ versus ‘machine,'” said Marasco, head of the Bionic Integration Laboratory at the Cleveland Clinic Lerner Research Institute. “These findings have important implications for improving human-machine interactions and bring us closer than ever to provide amputations for people with complete restoration of natural arm function.”

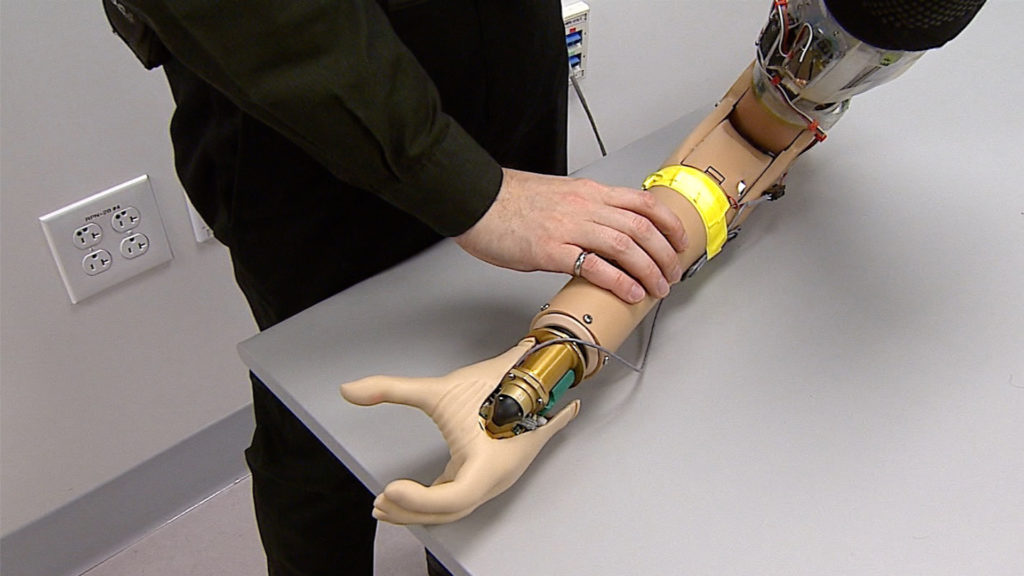

The team used small but powerful robots to vibrate specific muscles, to “activate” the sensation of movement of the patients, allowing them to feel that their fingers and hands were moving and that they were an integrated part of their own body. By feeling their lost hands while controlling their bionic prostheses, the patients in the study could make complex grip patterns to perform specific tasks as well or better than healthy people.

“Decades of research have shown that muscles need to feel the movement to function properly. This system pirates the neural circuits behind that system,” said James W. Gnadt, Ph.D., program director at the National Institute of Disorders Neurological and Stroke, part of the National Institutes of Health, which partially supported the study. “This approach takes the field of prosthetic medicine to a new level that we hope will improve the lives of many.”

To improve the relationship between the mind and the prosthesis, they investigated whether they could use an illusion of movement to help patients better control their bionic hands. They studied six patients who had previously undergone directed nerve reinnervation, a procedure that establishes a neuronal-machine interface by redirecting the amputated nerves to the remaining muscles. When patients’ reinvented muscles vibrated to provide illusory movement, they not only felt that their absent limbs were moving but could use these sensations to manipulate their prostheses intentionally and guide them accurately.

This is important because when a healthy person moves, the brain constantly receives comments about the progress of the movement. This unconscious sense prevents errors in movement, such as excessive range, and allows the body to make the necessary adjustments. However, people with amputation lose this essential feedback and, as a result, cannot control their prostheses without having to watch them carefully at all times.

The new study shows that the sensation of movement of the absent limbs, caused by strategic muscle vibration, provided patients with better spatial awareness and better control of the fine motor without visually controlling the prostheses. In addition, the sensation of movement made the bionic arms feel more like “me.”

“When you make a movement and then feel that it happens, you intrinsically know that you are the author of that movement and that you have a sense of control or ‘agency’ over your actions,” said Marasco. “People who have had an amputation lose that sense of control, which makes them feel frustrated and disconnected from their prostheses. The illusions we generate restore the sense of movement and restore their sense of agency over their prostheses. This helps people with amputation to feel more in control. ”

In the future, the research team is exploring ways to expand these techniques to patients who have lost a leg, as well as to those with conditions that inhibit the sensation of movement, such as stroke. They are also working on packaging the system into a prosthesis for longer-term applications that allow patients to operate the system daily.

“The ultimate goal of our research is to use the sensation of movement to optimize the relationship between patients and their technology, to better integrate their prostheses as a natural part of themselves,” said Marasco.

Marasco is a principal investigator at the Advanced Platform Technology Research Center, the Louis Stokes Medical Center of the Cleveland Department of Veterans Affairs and an associate scientist in the Department of Biomedical Engineering at the Cleveland Clinic Lerner Research Institute. In 2016, he received a Presidential Early Career Award for Scientists and Engineers from former President Barack Obama.

Co-authors of the study included Jacqueline Hebert of the University of Alberta; Jon Sensinger of the University of New Brunswick; Ravi Nataraj of the Stevens Institute of Technology; and Brett Mensh of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.